Key Takeaways

- The Fight Moved: McGirt was about criminal jurisdiction. The litigation that matters now involves taxation, municipal enforcement, environmental regulation, and business disputes.

- Analysis Is Layered: Who the parties are, what type of land is involved, and what kind of authority is being exercised all affect the answer. Simple rules don't exist.

- Compacts Are the Future: The jurisdictional questions being resolved constructively are the ones addressed through negotiated agreements between tribes and the state, not litigation.

After McGirt, most attention focused on what happens when a tribal member commits a major crime within reservation boundaries. That's important, but it's not where the practical action is. The litigation that's shaping Oklahoma's future involves questions most people never think about until they're directly affected: Who can issue a traffic ticket on this road? Whose environmental permits does this project need? Which court handles a contract dispute with a tribal enterprise?

Civil and regulatory jurisdiction doesn't generate the same headlines as criminal jurisdiction, but it touches more people's daily lives and affects more money. This is where the law is actually being made.

The Tenth Circuit's Role

Most of the significant civil jurisdiction litigation ends up in federal court—and for Oklahoma, that means the Tenth Circuit. Federal courts hear these cases because they involve federal questions about Indian Country status, tribal sovereignty, and the scope of state authority within reservation boundaries.

The Tenth Circuit's decisions shape the operating environment for everyone doing business in eastern Oklahoma. When the court rules on whether a municipality can enforce traffic laws against tribal members, or whether state environmental permits are required for projects on trust land, or whether tribal court judgments must be recognized in state court, those rulings create the framework that tribes, businesses, and state agencies work within.

The pattern over the last few years has been gradual clarification through case-specific rulings rather than sweeping pronouncements. Each decision addresses a particular fact pattern, and the general principles emerge over time.

Where the Disputes Happen

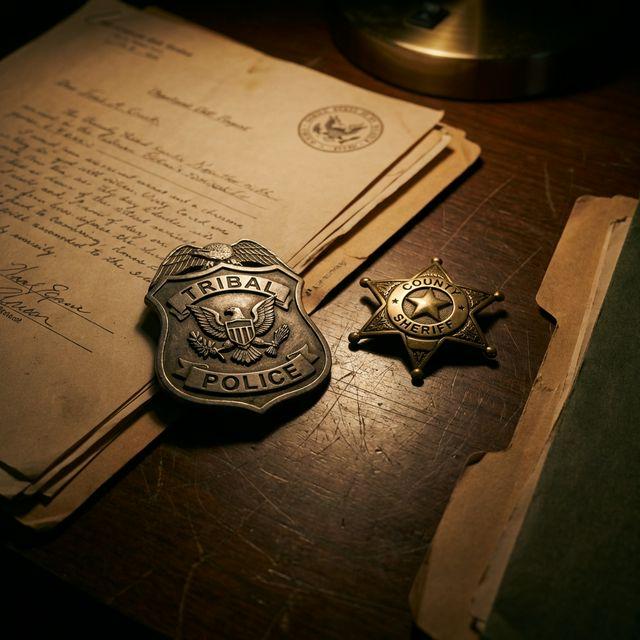

Municipal enforcement has generated more litigation than you might expect. Traffic citations, code enforcement, and city regulatory authority become jurisdictional battles when the person being cited is a tribal member on reservation land. These cases look small individually—someone contesting a ticket—but they establish precedents about who governs whom.

Taxation involves larger stakes. State income taxes, sales taxes, motor fuel taxes, and tobacco taxes all implicate questions about tribal versus state authority. Even when everyone agrees the land is within reservation boundaries, the outcome can depend on what type of tax it is, who's paying it, and what agreements exist between the tribe and the state.

Environmental regulation brings different complexity. Federal environmental law is heavily involved, and tribes can seek "treatment as state" status under various statutes, giving them direct regulatory authority. Questions about permitting, water quality, and natural resource management often involve overlapping federal, state, and tribal authority.

Business regulation and civil disputes raise forum questions. If you have a contract dispute with a tribal enterprise, or an employment claim arising within Indian Country, or a tort claim from an incident on reservation land, you need to know which court has jurisdiction and which law applies. The answers aren't always obvious.

The Montana Problem

A large percentage of civil jurisdiction disputes come down to one question: Can tribes exercise regulatory or adjudicatory authority over nonmembers on non-Indian fee land within reservation boundaries?

Federal law's default answer is no—with exceptions. Tribes have authority over nonmembers who enter consensual commercial relationships with the tribe or its members. Tribes have authority when nonmember conduct directly threatens tribal health, welfare, or self-governance. But outside those exceptions, nonmember activity on fee land generally falls outside tribal civil jurisdiction.

This framework creates most of the hard cases. The easy cases—tribal member on trust land, or clearly commercial relationship with the tribe—resolve relatively quickly. The edge cases—nonmember on fee land with arguable connection to tribal interests—generate litigation and uncertainty.

What's Being Resolved Through Negotiation

Not everything goes to court. Some of the most important jurisdictional questions are being resolved through compacts and intergovernmental agreements between tribes and the state.

Tax compacts address specific taxes with specific allocation formulas. Cross-deputization agreements address law enforcement. Regulatory cooperation agreements address environmental and public health matters. These agreements don't make the news, but they create practical frameworks that allow governments to operate without constant litigation.

The trajectory is toward more of these agreements, not fewer. Litigation is expensive and slow. Negotiated solutions can be tailored to specific situations and adjusted as circumstances change. Tribes and the state both have incentives to find workable arrangements rather than litigating everything.

What This Means for Businesses

For businesses operating in eastern Oklahoma, civil jurisdiction complexity is now a permanent feature of the environment. The question isn't whether you'll encounter jurisdictional questions—it's how you'll handle them when they arise.

Contract drafting matters more than it used to. Forum selection, choice of law, and dispute resolution provisions need to account for the reality that multiple legal systems may have plausible claims to jurisdiction. Contracts drafted before McGirt that assumed state court was the only relevant forum may not work the way the parties expected.

Regulatory compliance may require engaging with multiple authorities. Which permits you need, which inspections you're subject to, and which agencies have enforcement authority may depend on details about land status and the nature of your operations. The prudent approach is to understand the landscape rather than assuming you know the answer.

And relationships matter. Businesses that have constructive working relationships with tribal governments navigate this environment more successfully than businesses that view tribal authority as something to be avoided or minimized.

The Statutory Framework Behind These Disputes

Understanding the statutory framework is essential for anyone navigating post-McGirt civil jurisdiction. The definition of "Indian Country" under 18 U.S.C. § 1151 determines where tribal sovereignty applies. The Indian Commerce Clause gives Congress plenary power over Indian affairs, and statutes like 25 U.S.C. § 1301 define the scope of tribal governmental powers, including civil and regulatory authority over activities within reservation boundaries.

Environmental disputes often turn on the Clean Water Act and Clean Air Act provisions allowing tribes to seek "treatment as state" status under 33 U.S.C. § 1377 and 42 U.S.C. § 7474, giving them direct regulatory authority. Taxation disputes involve the interplay between state tax law and tribal sovereign immunity, with the Supreme Court's framework from Oklahoma Tax Commission v. Citizen Band Potawatomi Indian Tribe still guiding analysis.

For businesses, understanding these statutes—and how tribal sovereignty shapes business agreements—is not optional. It's the cost of operating in a jurisdiction where multiple sovereigns exercise concurrent authority. Those seeking practical guidance on cross-jurisdictional issues between tribal and state courts should consult counsel experienced in federal Indian law.

The Long View

McGirt forced Oklahoma to confront a legal reality that had existed for over a century. The reservations were never disestablished. Tribal sovereignty within those boundaries was never extinguished. The question is how state, tribal, and federal authority interact going forward.

That question won't be fully resolved for years. Litigation will continue to clarify specific issues. Compacts will address practical problems. Legislation may create new frameworks. The operating environment in 2030 will look different than it does today.

What won't change is the basic reality: tribal sovereignty is real, reservation boundaries matter, and civil jurisdiction is more complex than it used to be. Businesses and individuals who understand this and plan accordingly will do better than those who keep expecting the complexity to go away.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does McGirt affect civil cases or just criminal cases?

Both. While McGirt specifically addressed criminal jurisdiction, its recognition of reservation boundaries has significant civil implications — including questions about taxation, business regulation, environmental permitting, and family law jurisdiction.

Do non-Indians living on tribal reservations follow tribal law?

Generally, tribal civil jurisdiction over non-Indians is limited but not nonexistent. Tribes can exercise jurisdiction over non-Indians who enter consensual relationships with tribes or tribal members (like contracts), or whose conduct on tribal land threatens tribal health, welfare, or self-governance.

How are tribes and Oklahoma resolving jurisdictional overlaps?

Through a combination of litigation and Tribal-State Compacts. These compacts address specific overlapping areas like taxation, regulation, and law enforcement cooperation, creating practical frameworks while larger legal questions continue through the courts.

Will this eventually get "settled" or reversed?

The underlying McGirt holding — that these reservations were never disestablished — is established precedent. While Congress could theoretically act, and specific jurisdictional questions will continue to be litigated, the basic reality of reservation status is unlikely to change.

Navigating Post-McGirt Jurisdiction?

Civil jurisdiction in Indian Country is evolving rapidly. We track these developments closely and advise on structuring operations within reservation boundaries.

Learn How We Can Help →This article is for general information only and is not legal advice.