Key Takeaways

- Cross-Deputization Bridges Jurisdictional Gaps: These agreements allow tribal and state/local officers to enforce each other's laws, preventing criminals from exploiting the boundaries between tribal and state jurisdiction.

- Sovereignty Must Be Carefully Protected: Poorly drafted agreements can erode tribal self-governance by subordinating tribal officers to state authority or waiving sovereign immunity without adequate safeguards.

- Post-McGirt Oklahoma Makes These Agreements Essential: With roughly half of Oklahoma recognized as Indian Country, the need for cooperative law enforcement — and the risks of getting cooperation wrong — have never been greater.

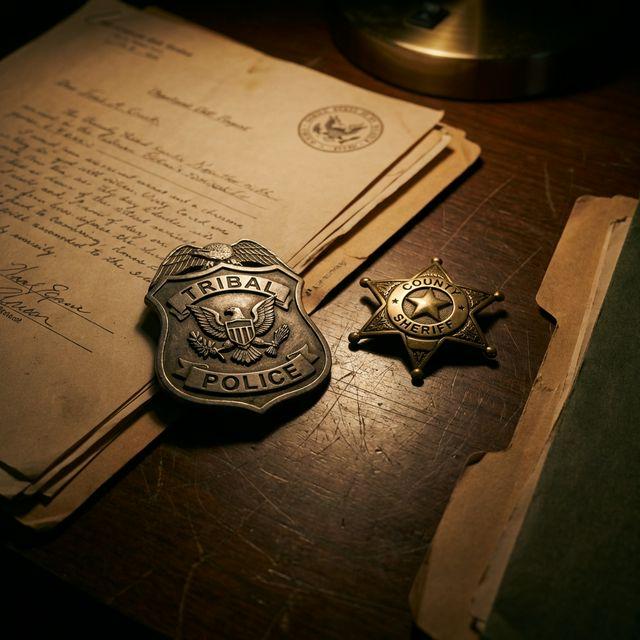

A drunk driver crashes on a state highway that passes through tribal land. A tribal Lighthorse officer is first on scene while the county sheriff is forty minutes away. A domestic violence call comes in from a home in Indian Country, but the victim is non-Indian and the tribal police department isn't sure it has jurisdiction. A county deputy pursues a suspect across a reservation boundary and suddenly doesn't know whether the arrest will hold up in court. These are not hypothetical scenarios. In post-McGirt Oklahoma, where roughly half the state has been recognized as Indian Country, they happen every day.

Cross-deputization agreements — also called cross-commissioning agreements or mutual aid compacts — are the primary legal mechanism for addressing these jurisdictional gaps. They allow officers from one sovereign (tribal, state, local, or federal) to exercise law enforcement authority on behalf of another. Done well, they protect public safety and respect tribal sovereignty. Done poorly, they erode self-governance, create liability nightmares, and leave everyone less safe.

What Cross-Deputization Actually Means

At its core, cross-deputization is an agreement between two or more law enforcement agencies — typically a tribal police department and a county sheriff's office, municipal police department, or state agency — that grants each agency's officers the legal authority to enforce the other's laws within specified boundaries.

In a typical arrangement, tribal Lighthorse officers receive commissions from the county or state, allowing them to enforce state law, make state-law arrests, and interact with non-Indians in Indian Country. In return, county or municipal officers receive tribal commissions, granting them authority to enforce tribal law and exercise jurisdiction over tribal citizens within reservation boundaries.

The legal basis for these agreements varies. Some are authorized by specific federal statutes. The Indian Law Enforcement Reform Act (25 U.S.C. § 2801 et seq.) authorizes the Bureau of Indian Affairs to enter cooperative agreements with tribal and state agencies. Some tribes have specific statutory or constitutional authority to enter law enforcement compacts. In Oklahoma, the framework has evolved rapidly in the wake of McGirt v. Oklahoma (2020), with the state, tribes, and local agencies negotiating agreements under a combination of state and tribal authority.

The agreements themselves are not standardized. They range from simple memoranda of understanding to complex intergovernmental compacts that address jurisdiction, liability, training, oversight, use of force policies, reporting requirements, and dispute resolution. The quality and specificity of these agreements matters enormously — both for public safety and for tribal sovereignty.

The Post-McGirt Imperative

Before McGirt v. Oklahoma, the jurisdictional landscape in much of Oklahoma was straightforward (if legally incorrect): state and local law enforcement exercised broad criminal jurisdiction across the state, including within reservation boundaries. McGirt changed that by holding that the Muscogee (Creek) Nation's reservation had never been disestablished, and subsequent decisions extended that recognition to the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, and Quapaw reservations.

Under the Major Crimes Act (18 U.S.C. § 1153) and the General Crimes Act (18 U.S.C. § 1152), criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country follows a complex framework based on the identity of the victim and perpetrator. When an Indian commits a crime against another Indian in Indian Country, only tribal and federal authorities have jurisdiction — the state is excluded. When a non-Indian commits a crime against an Indian, the federal government has exclusive jurisdiction. Only when a non-Indian commits a crime against another non-Indian does state jurisdiction clearly apply.

This created an immediate public safety problem. County sheriffs who had been handling all criminal matters within their counties — including on reservation land — suddenly lacked jurisdiction over a substantial portion of those cases. Tribal police departments, many already stretched thin, faced a surge in demand. Federal law enforcement (the FBI and BIA) didn't have the manpower to absorb the caseload. Crimes went uninvestigated. Suspects were released. Communities on both sides of the jurisdictional line were less safe.

Cross-deputization agreements emerged as the practical solution. By granting reciprocal authority, they allow the officer who arrives first — regardless of which sovereign employs them — to act. A tribal officer commissioned by the county can arrest a non-Indian suspect. A county deputy commissioned by the tribe can arrest a tribal citizen. The jurisdictional gaps close, and public safety improves.

The Benefits of Well-Crafted Agreements

When cross-deputization agreements are negotiated thoughtfully and implemented properly, the benefits are substantial.

The most immediate benefit is seamless emergency response. When a violent crime is in progress, the public doesn't care which sovereign employs the officer who responds — they care that someone responds. Cross-deputized officers can act immediately without first conducting a jurisdictional analysis. They can make arrests, secure crime scenes, protect victims, and preserve evidence regardless of which side of a jurisdictional line they happen to be on.

These agreements also enable continuity of investigation. Criminal investigations frequently cross jurisdictional boundaries. A suspect who commits a crime in Indian Country may flee to non-Indian land, or vice versa. Witnesses, evidence, and crime scenes may span multiple jurisdictions. Cross-deputized officers can follow an investigation wherever it leads without hitting a jurisdictional wall.

Cooperation builds community trust. When tribal citizens see tribal officers working alongside county deputies — as partners rather than adversaries — it reinforces the message that law enforcement serves the entire community. This is particularly important in parts of Oklahoma where historical distrust between tribal communities and state authorities runs deep.

Finally, cross-deputization allows for resource sharing. Most tribal police departments and rural Oklahoma sheriff's offices are underfunded and understaffed. Sharing officers, dispatch systems, training programs, and equipment makes both agencies more effective than either could be alone.

The Sovereignty Risks

Cross-deputization agreements are not without risk, particularly for tribal nations. Tribal sovereignty — the inherent right of tribes to govern themselves — is the foundation of the government-to-government relationship between tribes and the United States. Law enforcement is one of the most fundamental expressions of that sovereignty. When tribes enter into agreements that share or delegate law enforcement authority, they must ensure they are not giving away more than they're getting.

The most significant risk is subordination of tribal authority. If an agreement is structured so that tribal officers routinely act under state authority, they may effectively become agents of the state within Indian Country. This can undermine the tribe's ability to enforce its own laws, set its own law enforcement priorities, and maintain its own standards for policing. It can also create situations where tribal officers are enforcing state laws that conflict with tribal values or priorities.

Liability exposure is another major concern. When a cross-deputized officer uses excessive force or violates someone's rights, the question of which sovereign is liable becomes intensely contested. As the recent cases discussed in our analysis of cross-commissioned officers and Section 1983 liability demonstrate, federal courts have held that officers acting under tribal authority may be shielded from Section 1983 civil rights claims. This may seem advantageous for municipalities whose officers hold tribal commissions, but it creates a civil rights gap for victims and can ultimately erode public trust in law enforcement on all sides.

Sovereign immunity — one of the most important protections tribal nations possess — can be implicated by cross-deputization agreements. If an agreement waives tribal sovereign immunity (explicitly or implicitly) to allow claims arising from cross-deputized officers' conduct, the tribe may have opened itself to litigation it never intended. Every agreement should be scrutinized for language that could be construed as a waiver.

There is also the risk of mission creep. An agreement initially designed to address emergency response gaps can gradually expand into routine policing functions, with state officers exercising day-to-day authority within Indian Country that was never contemplated in the original agreement. Without clear boundaries, sunset provisions, and regular review, these agreements can drift far from their intended scope.

What Good Agreements Include

The best cross-deputization agreements share several characteristics that protect both public safety and sovereignty.

Clear jurisdictional boundaries define exactly when and where cross-deputized authority applies: emergency response only, or all criminal law enforcement? Major crimes only, or traffic stops too? Within a specific geographic area, or throughout the entire reservation? The more specific these boundaries, the less room for confusion and abuse.

Robust training requirements ensure that officers exercising cross-deputized authority understand the laws they're enforcing, the cultural context of the communities they're policing, and the limits of their authority. A county deputy with a tribal commission should receive meaningful training in tribal law, tribal court procedures, and the rights of tribal citizens — not just a piece of paper.

Accountability mechanisms specify how complaints against cross-deputized officers will be handled, which sovereign has disciplinary authority, and how disputes between agencies will be resolved. These provisions are critical because they determine what happens when things go wrong — and things inevitably go wrong.

Liability allocation provisions clarify which sovereign bears financial responsibility for claims arising from a cross-deputized officer's conduct. Without these provisions, victims of officer misconduct may find themselves in a jurisdictional no-man's-land where neither sovereign accepts responsibility.

Sunset and review provisions ensure that agreements are periodically renegotiated to reflect changing circumstances, lessons learned, and evolving community needs. A five-year term with mandatory review is far superior to a perpetual agreement that no one revisits.

Data sharing and reporting requirements ensure that both agencies know what the other is doing within their jurisdiction. Tribal nations should know how many arrests state officers make within Indian Country, what force is used, and what outcomes result. Without this information, meaningful oversight is impossible.

The Federal Role

The federal government plays an important but often insufficient role in cross-deputization. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) can enter into cooperative agreements directly and can facilitate agreements between tribal and state agencies. The Department of Justice has encouraged cross-deputization as a means of addressing public safety gaps in Indian Country.

However, federal resources have not kept pace with need. When McGirt recognized vast areas of Oklahoma as Indian Country, federal law enforcement did not proportionally increase its presence. The FBI's Oklahoma offices were not staffed to handle the volume of Indian Country criminal cases that resulted. This resource gap is a major driver of cross-deputization — tribes and states are cooperating in part because the federal government is not providing the alternative.

Federal legislation could help. Proposals to provide dedicated funding for tribal law enforcement, standardize cross-deputization frameworks, and clarify the civil rights landscape for cross-deputized officers have been discussed but not enacted. Until Congress acts, the framework will continue to be built agreement by agreement, tribe by tribe, county by county.

Implications for Local Government

Counties and municipalities entering cross-deputization agreements also need to understand the implications. Their officers will be acting under a second sovereign's authority — with all the legal complexity that entails. Training must reflect this dual role. Insurance coverage must account for the additional exposure. Policies on use of force, arrest procedures, and evidence handling must be reconciled between the two agencies' standards.

Municipal liability under Monell v. Department of Social Services may also be affected. If a city's policy of cross-commissioning officers with tribal agencies leads to constitutional violations, the city could face Section 1983 liability for that policy. Cities should ensure their agreements include adequate indemnification provisions and that their officers are properly trained on the scope and limits of their cross-deputized authority.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between cross-deputization and cross-commissioning?

The terms are largely interchangeable in practice. "Cross-deputization" typically refers to agreements between county/local agencies (reflecting the "deputy" terminology), while "cross-commissioning" is used when tribal agencies grant commissions to state or local officers. Both describe the same fundamental concept: granting an officer from one sovereign the legal authority to enforce the laws of another.

Can a cross-deputized officer arrest anyone, anywhere?

No. The scope of authority depends entirely on the specific agreement. Some agreements are broad, granting full law enforcement authority throughout the other sovereign's jurisdiction. Others are narrow, limiting cross-deputized authority to emergency situations, specific geographic areas, or specific types of crimes. Officers must understand the terms of their commission.

What happens if a cross-deputized tribal officer violates someone's constitutional rights?

This is an evolving area of law. Recent Oklahoma federal court decisions suggest that officers acting under tribal authority may not be subject to Section 1983 civil rights claims, which require "state action." Other remedies — tribal court claims under the Indian Civil Rights Act, state tort claims, and internal disciplinary proceedings — may still be available.

Do all Oklahoma tribes have cross-deputization agreements?

No. Cross-deputization agreements are negotiated individually between specific tribes and specific local agencies. Some tribes have extensive agreements with multiple counties; others have none. The landscape is patchwork, and the quality and scope of agreements varies significantly.

Can a tribe revoke a cross-deputization agreement?

Generally, yes — subject to the terms of the agreement itself. Most agreements include provisions for termination by either party with notice. Tribes retain the sovereign right to determine who exercises law enforcement authority within their jurisdiction, and they can revoke individual commissions or terminate the entire agreement if it no longer serves their interests.

How does cross-deputization affect tribal sovereignty?

It depends entirely on how the agreement is structured. A well-crafted agreement that preserves tribal control over law enforcement priorities, maintains accountability mechanisms, and includes sunset provisions can strengthen sovereignty by demonstrating effective self-governance. A poorly crafted agreement that subordinates tribal officers to state authority, waives sovereign immunity, or allows unchecked state policing within Indian Country can significantly erode sovereignty.

Are cross-deputization agreements public records?

Generally, yes — at least the agreements entered into by state and local agencies are subject to the Oklahoma Open Records Act. Tribal governments may or may not make their agreements publicly available, depending on tribal law and policy.

Cross-deputization agreements are not new, but their importance in Oklahoma has never been greater. In the post-McGirt landscape, they are the primary mechanism preventing jurisdictional gaps from becoming public safety crises. But they must be crafted with care — protecting both the communities they serve and the sovereignty of the tribal nations that enter them.

At Addison Law, we advise tribal governments and businesses on sovereignty and governance issues, including law enforcement agreements, intergovernmental compacts, and the civil rights implications of cross-deputization. Contact us for a consultation.

Navigating Tribal Law Enforcement Agreements?

Cross-deputization agreements implicate sovereignty, liability, and civil rights. Get guidance from attorneys who understand federal Indian law.

Schedule a Consultation →This article is for general information only and is not legal advice.