Key Takeaways

- Early Identification Is Everything: ICWA applies based on the child's status, not the parents' preferences. Inquiry must happen at the outset of every child custody proceeding, not after placements are made.

- Active Efforts Means Active: "Active efforts" to prevent family breakup is a higher standard than "reasonable efforts." Courts that conflate the two make reversible error.

- Tribes Have Independent Rights: The child's tribe can intervene, transfer jurisdiction, and invalidate proceedings that didn't comply with ICWA — even years later.

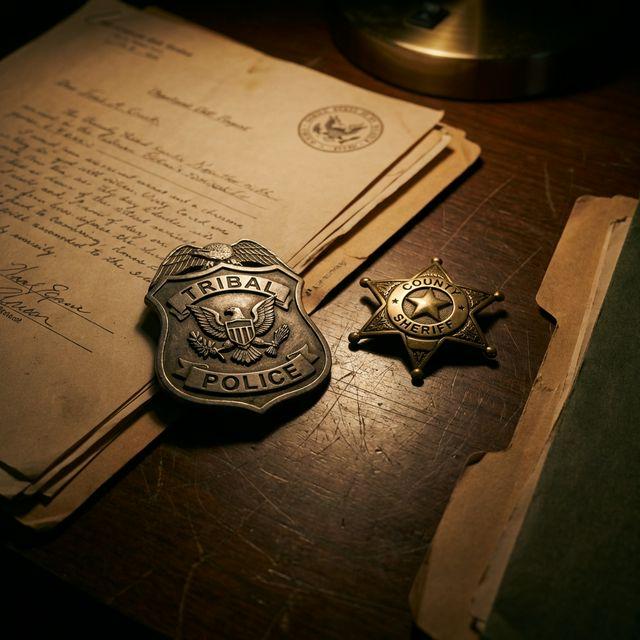

Two years after the adoption was finalized, the tribe files a motion to invalidate. The adoptive parents are devastated. The agency insists it followed the rules. But somewhere in the case file is evidence that someone knew about the child's tribal heritage and didn't follow through — a note about the biological father's enrollment, a mention of tribal ancestry that never triggered proper notice. Now everyone is in court again, and the child's stability hangs on whether the original proceeding was properly conducted.

This scenario isn't hypothetical. ICWA violations can surface years after proceedings conclude, because the statute provides broad grounds for invalidation when its requirements aren't met. The Indian Child Welfare Act, codified at 25 U.S.C. § 1901 et seq., establishes federal standards that override state law in child welfare proceedings involving Indian children — and practitioners who treat it as a paperwork formality rather than a federal mandate with real consequences put their cases, their clients, and most importantly the children at serious risk.

Why ICWA Exists

The Indian Child Welfare Act was Congress's response to a documented crisis: Native American children were being removed from their families and communities at rates vastly disproportionate to non-Native children, often without adequate justification and in deliberate disregard of tribal interests in their members' welfare. Studies at the time showed that approximately 25% to 35% of all Indian children were being placed in foster care, adoptive homes, or institutions — the overwhelming majority in non-Indian placements that severed the children's connections to their tribal identity, culture, and community.

ICWA established federal standards for foster care placement, termination of parental rights, and adoption of Indian children. It requires specific procedures, imposes heightened evidentiary standards beyond those in general child welfare law, and gives tribes rights to participate in proceedings affecting their children. Understanding this context matters for every practitioner. ICWA isn't an obstacle to child welfare proceedings — it is a recognition that the child welfare system has a documented history of failing Native children and families, and that federal standards are necessary to prevent that failure from continuing.

The Threshold Question: Is This Child an "Indian Child"?

ICWA applies to "Indian children" — unmarried persons under 18 who are either members of a federally recognized tribe or eligible for membership and have a biological parent who is a member. The critical point that practitioners frequently miss is that the tribe determines membership eligibility, not the court and not the parties. A child whose parents deny tribal heritage may still be an Indian child if the tribe says so. A child who has never lived on a reservation, never participated in tribal culture, and has no subjective connection to tribal identity may still qualify if the eligibility criteria are met.

This is why inquiry is mandatory. Courts must ask, at the outset of any child custody proceeding, whether there is reason to believe the child may be an Indian child. This isn't a formality to skip when the answer seems obvious. The consequences of getting it wrong — proceeding without ICWA protections when they should have applied — can undo years of proceedings and placements. The inquiry obligation falls on both the court and the agency, not on the parents to volunteer the information.

Notice Requirements: Where Cases Go Wrong

When a court knows or has reason to know that an Indian child is involved, ICWA mandates notice to the child's tribe. This notice must be sent by registered mail at least ten days before any foster care placement hearing or termination of parental rights proceeding. The notice serves multiple purposes simultaneously: it gives the tribe the opportunity to verify the child's enrollment status, allows the tribe to exercise its right to intervene in the proceeding, and ensures the tribe can consider whether to seek transfer of jurisdiction to tribal court.

Defective notice is one of the most common ICWA errors — and one of the most consequential. Proceedings conducted without proper notice are subject to invalidation, regardless of how much time has passed or how well-established the placement has become. A finalized adoption that didn't include proper tribal notice remains vulnerable to challenge for as long as the statute's invalidation provisions apply. This is not a technicality. It is the mechanism through which Congress ensured that tribes would have the opportunity to participate in proceedings affecting their youngest and most vulnerable members.

Active Efforts: The Higher Standard

Before any foster care placement or termination of parental rights, ICWA requires a finding that "active efforts" have been made to provide remedial services and rehabilitative programs designed to prevent the breakup of the Indian family. This standard is explicitly higher than the "reasonable efforts" required by general child welfare law, and courts that conflate the two are making reversible error.

Active efforts means just that — active, affirmative steps tailored to the family's specific circumstances, not passive service offerings that the family failed to pursue. What qualifies depends on context, but generally includes engaging the tribe in case planning, providing culturally appropriate services, pursuing resources specific to the family's needs, and making persistent efforts to engage family members even when they are difficult to reach or resistant to participation. Courts that simply check whether the same standard menu of services offered in every non-ICWA case was also offered here are applying the wrong standard and creating a record vulnerable to reversal.

The distinction between active and reasonable efforts has practical significance beyond legal semantics. Active efforts require the agency to do more — to go further, try harder, and engage the tribe as a partner in developing a service plan that reflects the family's cultural context and community resources. When agencies approach this obligation genuinely rather than defensively, outcomes for families often improve because the services are actually tailored to what the family needs.

Placement Preferences

When placement outside the home is necessary, ICWA establishes preferences for where the child should be placed. For foster care, the preferences prioritize extended family members, foster homes licensed or approved by the child's tribe, Indian foster homes approved by another authorized non-Indian licensing authority, and institutions approved by the tribe or operated by an Indian organization. For adoptive placements, the preferences prioritize extended family, other members of the child's tribe, and other Indian families.

These preferences aren't absolute — good cause can justify deviation — but they are not optional suggestions either. Courts must consider the preferences, apply them, and document the basis for any departure. For prospective adoptive parents, this means understanding that ICWA may affect whether their adoption can proceed and, critically, whether it remains legally valid if the preferences weren't properly considered.

The Tribe's Independent Rights

One of the most frequently misunderstood aspects of ICWA is that tribes hold rights independent of the parents' wishes. A parent cannot waive the tribe's right to notice, intervention, or transfer of jurisdiction. A parent who consents to adoption does not eliminate ICWA requirements. This reflects Congress's recognition that tribes have distinct interests in proceedings affecting their children — interests beyond and independent of the individual parents' positions.

The child is not just a member of a family but a member of a tribal community with its own stake in the child's welfare and its own sovereignty interests at stake. For practitioners, this means the tribe must be engaged even when the parents express no interest in tribal involvement. Proceeding as if parental preferences control tribal rights creates invalidation risk that can surface years later when the tribe learns of the proceeding and exercises its independent standing to challenge it.

Post-Brackeen Landscape

In 2023, the Supreme Court upheld ICWA's constitutionality in Haaland v. Brackeen, rejecting arguments that the statute discriminates based on race or commandeers state agencies. This resolved the most fundamental constitutional challenges and affirmed that ICWA remains good law. But Brackeen didn't eliminate all questions — specific applications continue generating litigation over what constitutes "good cause" to deviate from placement preferences, what active efforts are required in particular circumstances, how to handle cases where tribal membership is disputed or delayed, and whether emerging technologies or practices affect notice requirements.

Practitioners who understand both the settled constitutional framework and the ongoing operational questions position their cases for the strongest possible outcomes — and protect the permanency that every child in these proceedings deserves.

At Addison Law, we handle ICWA cases from both tribal and non-tribal perspectives. Whether you're a tribal government seeking to protect your children's interests, a parent navigating ICWA requirements, or an agency ensuring compliance, we understand the law and its practical applications. Contact our tribal law practice or reach out directly to discuss your situation. We also advise on related tribal sovereignty matters including gaming compact negotiations and federal Indian law compliance.

Frequently Asked Questions

What triggers ICWA protections in a child welfare case?

ICWA applies whenever a state court proceeding involves the foster care placement, termination of parental rights, or pre-adoptive or adoptive placement of an Indian child — defined as a child who is a member of or eligible for membership in a federally recognized tribe. The inquiry obligation requires courts and agencies to investigate potential Indian status at the outset of every child welfare case.

Does ICWA apply to custody disputes between parents?

Generally, no. ICWA does not apply to custody disputes between parents in a divorce or separation. It applies specifically to child welfare proceedings where the state is seeking to remove a child from their parent or Indian custodian. Private custody disputes between parents, even when one parent is a tribal member, typically fall outside ICWA's scope.

What happens if ICWA requirements aren't followed?

An adoption or placement that fails to comply with ICWA can be invalidated — even years after finalization. This is why strict compliance is essential: it protects the permanency of outcomes for all parties, including the child, the adoptive family, and the tribe. An invalidated adoption is devastating for everyone involved, and the risk is entirely preventable through proper compliance.

Can a tribe intervene in a state child welfare case?

Yes. A child's tribe has the right to intervene at any point in a state court proceeding involving an Indian child. The tribe can also request transfer of the case to tribal court, which generally requires the state court to transfer unless good cause exists to deny the request or either parent objects.

Navigating an ICWA Case?

ICWA compliance protects children, families, and case outcomes. We handle these matters from both tribal and non-tribal perspectives.

Learn How We Can Help →This article is for general information only and is not legal advice.